Supply Chain Nightmares: 5 Real-Life Supplier Disasters

What do KFC, Honda, and Dior have in common?

Each faced a supplier disaster so epic it made headlines—and cost them dearly.

These aren’t theoretical risks or minor hiccups.

These are real-world examples of what happens when supplier relationships go wrong.

From spoiled chicken to counterfeit airbags, here’s what every procurement team can learn from five infamous supply chain fails.

“To put it simply, we’ve got the chicken, we’ve got the restaurants, but we’ve just had issues getting them together.”

That’s how, in February 2018, KFC tried to explain why it had to shut down more than 700 restaurants in the UK.

All because of a chicken shortage.

Well, not exactly. The real issue wasn’t the lack of chicken.

It was a supplier switch gone very, very wrong.

In late 2017, KFC replaced its long-time logistics partner, Bidvest, with DHL, despite warnings from the union.

Source: Google

The reason? Cost savings.

While Bidvest (now Best Food Logistics) specialized in chilled food logistics and ran a network of six regional depots, DHL had no experience with perishable goods and planned to run deliveries from a single distribution center.

Predictably, things unraveled fast.

In the first days DHL took over, an accident on the M6 brought traffic to a standstill, stranding delivery trucks and causing a massive backlog.

With just one depot to work from, DHL couldn’t recover quickly.

Fresh chicken never made it to the restaurants.

And the doors of more than 700 restaurants across the UK stayed shut.

Source: X

But it wasn’t just traffic or bad luck that led to this disaster.

According to experts, DHL was underprepared.

A new warehouse, a new IT system, poor planning, and a chaotic handover created what Samir Dani, Professor of Operations and Supply Chain Management, called a “perfect storm.”

Illustration: Veridion / Quote: Wired

Still, it wasn’t only DHL’s fault.

KFC had made the decision based on price without fully assessing the operational risks, as Dr. Virginia Spiegler of Kent Business School explains:

“KFC’s decision to switch its 3PL provider from Bidvest to DHL was a measure to reduce logistics service cost. However, having hundreds of restaurants closed could cost them millions in lost sales and low capacity utilization.”

In short, they got what they paid for.

Cheaper logistics, yes.

But also empty kitchens, irate franchisees, lost revenue, and reputational damage.

It’s a classic case of poor supplier evaluation and zero contingency planning.

Had KFC properly compared Bidvest’s capabilities with DHL’s, especially in handling perishable goods, this could likely have been avoided.

And the impact wasn’t just operational.

Customers showed no mercy.

Many walked straight into the arms of competitors or mocked KFC online.

Source: X

Some people even called the police to complain.

Yes, really.

It’s sweet, it’s garlicky, it’s got a slow-burning heat that creeps up just as you think you’re safe.

That’s the magic behind one of North America’s most beloved hot sauces: Sriracha.

But there’s no Sriracha without ripe red jalapeño peppers that are vibrant in color, full in flavor, and picked at just the right time.

And when it comes to the Sriracha, the one in the clear bottle with the green cap made by Huy Fong Foods, things have been heating up for all the wrong reasons.

It all started with a supplier breakup.

For nearly three decades, Huy Fong had a single, trusted partner: Underwood Ranches, a California farm that grew all of the company’s chili peppers.

It was a relationship that worked—until it didn’t.

Source: Fortune

In 2016, the two sides fell out over a payment dispute.

And it was costly, too.

Underwood won a $23 million lawsuit in 2019, and Huy Fong lost a supplier it had relied on for nearly 30 years.

What followed was years of instability for Huy Fong Foods: pepper shortages, inconsistent quality, and full production halts.

Since 2020, Huy Fong has paused Sriracha production at least three times due to a lack of ingredients.

They tried to move on with new suppliers. But it wasn’t that simple.

One year, the chili peppers arrived too green, as the company told wholesalers:

Illustration: Veridion / Quote: LA Times

Sriracha isn’t supposed to be murky brown or bright green. It’s meant to be that rich, fiery red that signals heat and flavor.

Even small variations in pepper ripeness changed the product’s color and taste, and Huy Fong wasn’t willing to compromise on quality.

But quality control wasn’t the only issue.

With limited suppliers and increasingly unpredictable growing conditions, like droughts in northern Mexico, Huy Fong was stuck.

They couldn’t pivot quickly, and they couldn’t keep up with demand.

Other hot sauce brands weathered the same climate conditions without major disruptions.

The difference? They had diversified their supplier base.

Huy Fong didn’t.

And they were likely locked into contracts with growers who simply couldn’t deliver, as David Ortega, professor of food, agriculture, and resource economics at Michigan State University, points out:

“While the core culprit may have been climate change, the fact that other hot sauce suppliers didn’t experience the same shortage meant that Huy Fong likely found itself locked into long-term contracts with growers that failed to deliver.”

Of course, the damage didn’t stop at the factory floor. It hit the people who serve and eat Sriracha, too.

When Golden Bell, a Vietnamese restaurant in Calgary, ran out of Huy Fong’s sauce for its most popular soup, they tried a different brand.

But customers noticed, says Taylie Nguyen, the restaurant’s manager:

Illustration: Veridion / Quote: CBC

Some walked out, and some just didn’t come back.

The story of the sriracha shortage is much more than a supply chain hiccup.

Rather, it’s the fallout of a broken relationship, one that had worked for nearly 30 years.

And it’s a cautionary tale. Because while most supply chain disasters start with the wrong supplier, this one started with the loss of the right one.

Lose a great supplier, and you risk losing everything that came with them—consistency, trust, and the product your customers actually love.

Years later, Huy Fong is still trying to rebuild what it once had.

But loyal customers are hard to win back, and red-hot peppers are apparently difficult to grow.

No list of supplier disasters is complete without Takata.

And no company took a harder hit than its biggest customer: Honda.

So, what happened?

Takata was once a giant in the automotive parts industry.

It began making airbags in 1988 and, by 2014, controlled 20% of the global market.

But behind that dominance was a fatal flaw—literally.

Takata airbags were built using a volatile chemical propellant: phase-stabilized ammonium nitrate.

Source: NY Times

In some inflators, that chemical became unstable over time, especially in humid or high-temperature environments.

This resulted in airbags that didn’t deploy but exploded.

Globally, more than 100 million vehicles were affected.

In the U.S. alone, 67 million Takata airbags were recalled across multiple automakers.

But no one was hit harder than Honda.

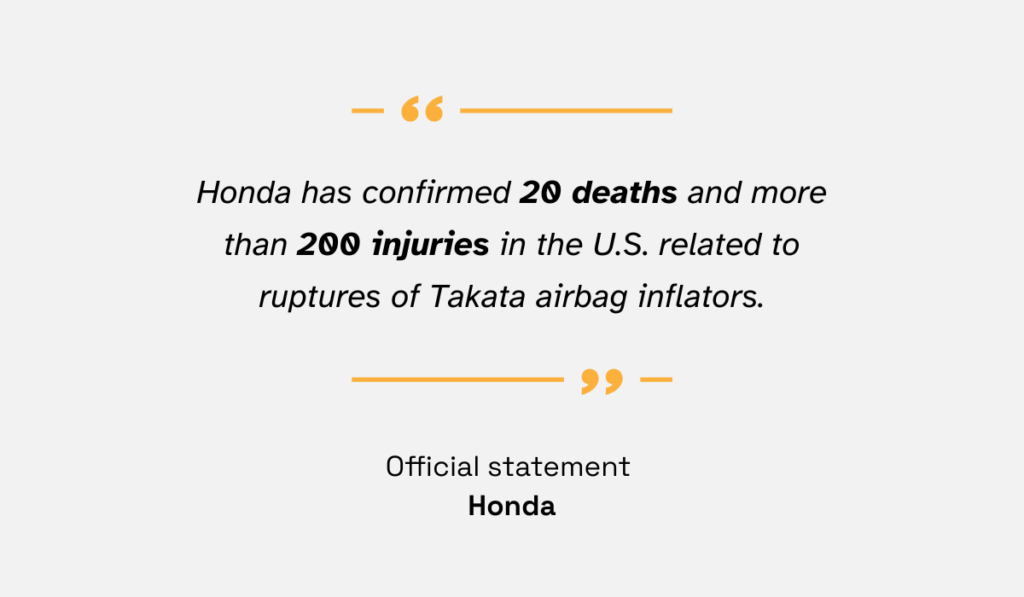

Illustration: Veridion / Quote: Honda News

And that’s just the U.S.

Honda also confirmed fatalities in Brazil, China, Ghana, Malaysia, Mexico, Pakistan, Seychelles, and Thailand.

What caused it all?

A toxic mix of poor testing, sloppy quality control, and corporate deception, Scott Upham, former CEO of Valient Market Research, summarized:

“The sad saga of Takata has resulted in the implosion of one of the automotive industry’s oldest and most successful suppliers due to technical hubris, mismanagement and a systemic corporate culture of manipulation.”

In 2017, Takata pleaded guilty to wire fraud in the U.S., admitting it had manipulated safety data and withheld key information for years, long after airbags began failing in real-world crashes.

The company was fined $1 billion, including $125 million to compensate victims. It filed for bankruptcy shortly after.

Source: CNN

For Honda, the cost was a slow-motion brand crisis that unraveled over years, and still isn’t fully over.

As Takata’s biggest customer, Honda recalled more than 30 million vehicles, and warned it might need to recall up to 21 million more.

The financial hit was brutal:

But worst of all, Honda became entangled in life-and-death failures that shook consumer trust.

Unlike the Huy Fong example, where a strong supplier relationship fell apart, this story is the opposite.

A supplier that looked strong, but hid dangerous weaknesses.

If anything, this example shows that it’s not enough for a supplier to deliver at scale.

They also have to deliver with integrity, transparency, and the kind of risk controls that protect both brands and customers.

Honda trusted Takata to build a life-saving device.

Instead, it became one of the largest safety recalls in automotive history, and a case study in how supplier failures can escalate into existential threats.

We’re still in the car industry, but this time, the threat wasn’t mechanical.

It came through a keyboard.

And as Cowbell’s Cyber Roundup Report 2024 reveals, that threat is becoming harder to ignore.

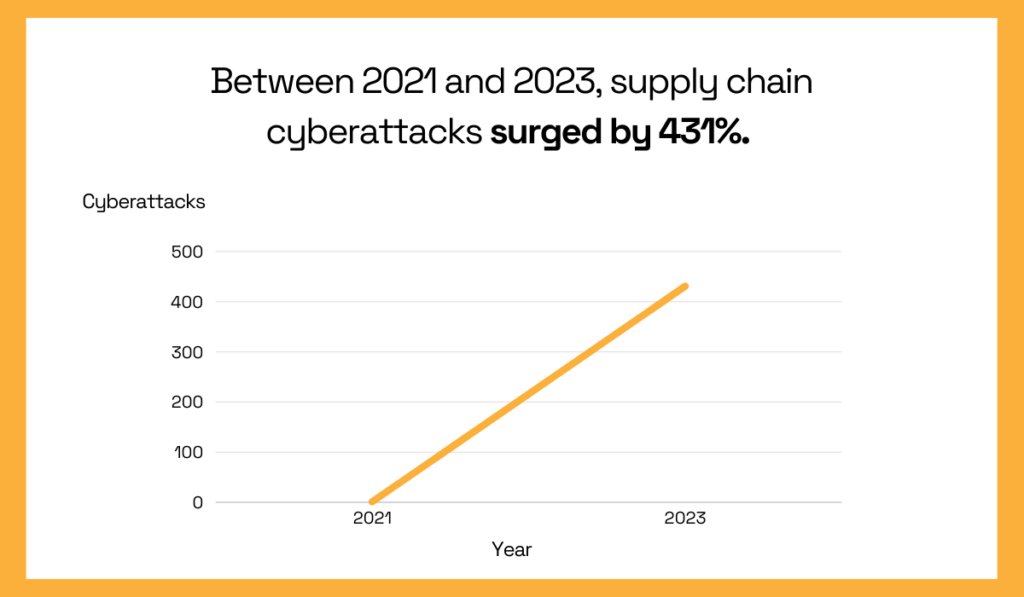

Namely, supply chain cyberattacks surged by 431% between 2021 and 2023.

Illustration: Veridion / Data: Cowbell

They’re effective because they don’t just target one company.

Instead, they exploit the trust between manufacturers and their suppliers, using one weak link to take down entire networks.

Toyota experienced this in 2022, when a cyberattack hit Kojima Industries, its relatively small supplier of plastic parts and electronic components.

Source: CPO Magazine

That single breach forced Toyota to shut down 28 production lines at 14 plants across Japan.

Toyota said in a public statement:

“Due to a system failure at a domestic supplier (KOJIMA INDUSTRIES CORPORATION), we have decided to suspend the operation of 28 lines at 14 plants in Japan on Tuesday, March 1st (both 1st and 2nd shifts). We apologize to our relevant suppliers and customers for any inconvenience this may cause.”

According to estimates, the attack cost Toyota roughly 13,000 vehicles in lost output, which is a 5% drop in monthly production.

But this exposed a deeper vulnerability.

Toyota has long been the poster child for Just-in-Time (JIT) manufacturing, a system where parts arrive exactly when needed, not before.

It’s efficient and lean, but also fragile.

Because there are no big stockpiles or excess inventory, when Kojima’s systems went down and parts couldn’t be delivered, there was nothing on hand to keep production running.

That’s the risk of JIT—it turns every supplier into a single point of failure.

And when that failure comes through a digital backdoor, the impact spreads even faster, Hank Schless, security expert and Director of Product Marketing at Lookout, points out:

Illustration: Veridion / Quote: CPO Magazine

And if we add the price of that downtime, estimated at $2.3 million per hour by Siemens, the cost of a single supplier breach quickly becomes a multi-million-dollar crisis.

Kojima may have been a small cog in a giant machine. But in Toyota’s hyper-efficient supply chain, that cog was critical.

Cyberattacks don’t have to hit the biggest players to cause the biggest damage.

All they need is a weak link and a network that’s too tightly coupled to withstand the snap.

In today’s connected supply chains, digital risk is supplier risk.

And Toyota’s experience is a reminder that supplier vetting needs to include cybersecurity, not just part quality or delivery speed.

If ESG once felt like a checkbox, today it’s a brand’s reputation.

And without real visibility beyond Tier 1 suppliers, even the most polished supply chains can hide ugly truths.

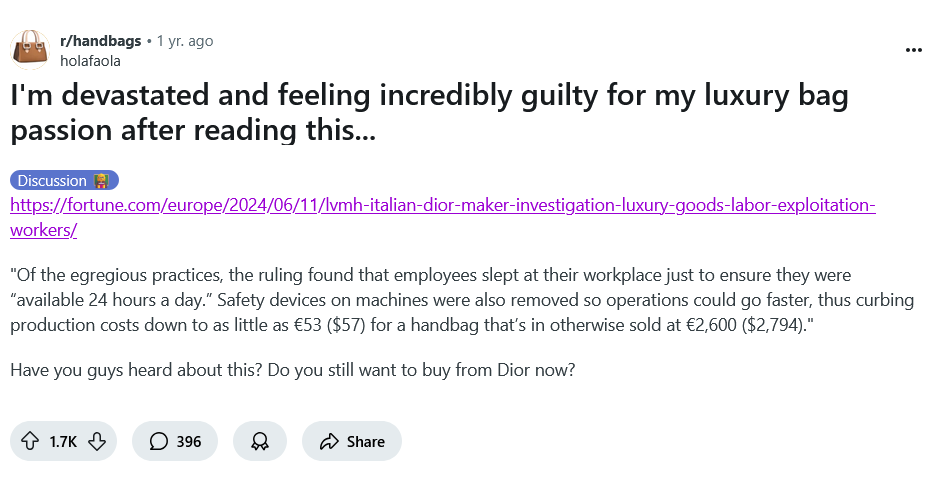

In 2024, Italian authorities placed Manufactures Dior, the local production arm of LVMH-owned Dior, under judicial administration after uncovering serious labor abuses.

Source: Fortune

The scandal wasn’t in a distant sweatshop, but in Italy’s luxury heartland.

Dior had outsourced handbag production to four small subcontractors, including AZ Operations and Pelletterie Elisabetta Yang.

What police found inside their workshops was staggering:

These factories were producing bags for just €53—Bags that Dior sells for over €2,600 in stores.

To make matters worse, AZ Operations had supposedly passed audits in January and July 2023, showing “no non-conformities.”

But a 2024 police inspection found the company was “de facto non-existent.”

Investigators revealed it was a shell for New Leather Italy, a Chinese-owned firm operating sweatshop-like conditions near Milan.

Another supplier, Pelletterie Elisabetta Yang, also passed a scheduled audit—yet a later police raid uncovered irregular workers and hidden living quarters.

Audits, Reuters found out, were scheduled in advance, giving suppliers time to clear premises and coach staff.

Source: Reuters

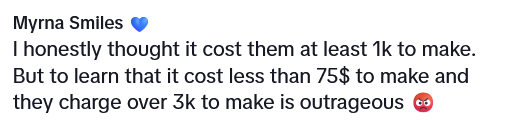

The public backlash was fierce.

TikTok users blasted Dior for charging thousands while paying pennies:

Source: TikTok

On Reddit, people expressed anger, regret, and even grief over buying Dior bags.

Source: Reddit

But Dior isn’t the only luxury fashion brand facing these allegations.

Recently, in May 2025, an Italian court placed Valentino under judicial administration for similar abuses.

In 2024, Armani also faced labor-related allegations.

The Dior scandal and all the other ones remind us that ESG isn’t just about what a brand says.

It’s about what happens at every tier of the supply chain, including the ones brands don’t want to look too closely at.

Supplier audits, if done poorly or infrequently, can’t protect workers or brands.

What’s needed is true supplier visibility, including sub-tier transparency, smarter due diligence, and ethical accountability from the top down.

Because in a world where luxury brands sell aspiration and identity, being caught ignoring abuse is not just a compliance issue.

It’s a brand killer.

Supply chain disasters don’t discriminate.

Whether it’s food, fashion, or factory parts, no industry is immune.

But every supply chain nightmare you’ve just read about could have been avoided with stronger supplier due diligence, diversified sourcing, and real visibility beyond Tier 1.

In an ESG-driven world, knowing who you work with (and who they work with) is the new baseline.

And more than ever, procurement can be a device to protect your brand, your customers, and your future.

Only if you look deeper and choose better suppliers from day one.

Veridion’s data for supplier discovery can help you here.